talk given at College Art Association, February 4, 2015, for panel Mapping Feminist Art Networks

update, I revisit this topic in the forthcoming essay "Feminist Artists and Network Analysis," Artlas

The analysis I’m sharing today is a follow up to my earlier work on feminist manifestos, an effort to stretch the genre of manifesto to incorporate a play written by a women’s liberation group and a broadsheet created for the Feminist Studio Workshop. At the same time I became interested in whether it was possible to use digital analysis to define or categorize documents as feminist manifestos, which was when I started to develop the methodology for the project I’m sharing with you today. When I saw Katy Deepwell of n.paradoxa’s anthology (and I’d like to acknowledge her path-breaking work putting feminist art history and criticism on the web) Feminist Art Manifestos, I couldn’t resist the temptation to pick back up this thread of my research.

Deepwell argues that “As a form of literature, manifestos occupy a specific place in the history of public discourse as a means to communicate radical ideas” to articulate “feminist politics as a set of “demands,” to explore “feminist art practices and poetics” and finally as “experiments in feminist aesthetics.” Deepwell’s anthology “concentrates on manifestos which are about feminist art production and film-making by feminist artists.” Beyond that the commonalities start to fragment. As she explains: “If they share anything, it would have to be defined very loosely by a common concern for women’s art practices, feminist politics and women’s creative potential as artists. … Each of these manifestos announce a different critique of the status quo, of patriarchy and currently proscribed roles for men and women in our society, including the very limited, often dismissive, view of the woman artist.”

While one might, as always, quibble with the editorial choices Deepwell made, utilizing her anthology offers an excellent place to start asking questions about feminist art manifestos, as well as conforming to a practice I adhere to in my digital work, bringing more than one scholarly voice into the selection of sources to be analysed. Initially I hoped to track the spread of feminist art manifestos through print, but that proved quite difficult. I’ll come back to the questions that difficulty raised in my conclusion. Let us turn then to the question at hand, what does digital analysis of the 35 manifestos included in Deepwell’s anthology tell us, either about feminist art or about the genre of manifesto? (full list appendix 1)

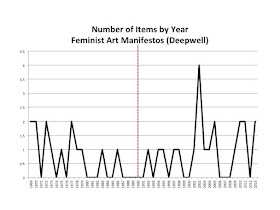

The documents span 1969 to 2013 but they are not evenly distributed. A prolonged gap exists from 1987 to 1991, which allowed for a chronological divide of pre- and post-1990s manifestos. The latter period has 60 percent of the items, but because the earlier items are longer, the two sets are roughly the same size by word count.

The first thing I did was to run something called a burst analysis on the texts of the manifestos. This analysis detects the emergence of words at specific dates within a set of documents. Two things proved fascinating. Male and men appeared almost completely contained in the earlier period. With a software for computational linguistics, I looked to see which documents contained men and male and how these words were used. As we might have expected, the very earliest manifestos, produced by artists now acknowledged as important figures in the feminist art movement contained a great deal of content that might be described as an oppositional or accusatory manifesto discourse.

Nancy Spero’s “Feminist Manifesto” produced c 1970-1971 begins “male/female relationships are essentially asymmetrical; men dominate women” while Carolee Schneemann’s visionary “Woman in the year 2000” (1977) hopes for a future when women artist will not “feel like … a belligerent whose devotion to creativity could only exist at the expense of a man, or men and their needs.” However, there are some fascinating finds as this discourse evolves as well, in perhaps lesser-discussed manifestos, such as the 1986 'There Have Always Been Great Blackwomen Artists' by Chila Burman, which begins by noting the “constraints which the white-male art establishment imposes” on Blackwomen artists, while pointing out as well that despite being the “staunchest allies of black men and white women” Blackwomen artists “have hardly ever received” support or recognition.

This relative decline in feminist art manifestos of the word men or male raises the question of what happened to this an oppositional discourse? Had disappeared it? I was also intrigued by the lack of bursts in the post 1990 period at all, no matter how the software settings were tweaked, which indicated relatively little in common in these documents as compared to the earlier documents.

I then turned to a semantic tagging software program to try to get to how the language and content of the manifestos shifted over time.

The earlier a document appeared, the more likely it was to contain woman or women and to a lesser degree feminist. (Note too that the similarities extend to 1992 further than the 1990 divide I initially selected ) These uses varied widely, however, from the Susan B Anthony Coven #1 invocation “feminist witch-mothers are women who seek the feminine principle within themselves and feel conjoined with the triple creatress as daughters” to the Guerilla Girls 2010 injunction “Use the F word. Be a feminist. For decades the majority of art school graduates have been women. “![]()

However, because there are many ways of talking about women and feminism beyond the use of these words, I also looked at semantic content. I ended up focusing on how much relative content was tagged about female people (YELLOW), art (BLACK), and obligation/necessity (RED) as a way to get at the relationship between demands made about women and art. In 1972 Export implored “let women speak so that they can find themselves, this is what I ask for in order to achieve a self-defined image of ourselves and thus a different view of the social function of women. we women must participate in the construction of reality via the building stones of media-communication”

As expected the earlier set of documents are fairly consistent in this content, but it certainly has not disappeared after that time. In fact art and obligation/necessity continue even as female people do so less. Do we then have then feminist art manifestos without women? In a sense yes. One quarter of the manifestos have no content tagged as “female persons” They are anchored in the mid 1990s to very first years of the 21st century. To those of us working on feminist art during that period, the early years of that era will be remembered as one of both considerable backlash against 1970s feminist art even as artists continued to explore feminist issues.

Two other hypotheses occurred to me, either authors no long feel the need to no need to hammer away at the message women can be artists, and thus less mention of women in general, or perhaps there might be a relationship of form and content.

![]()

I categorized the manifestos into three forms, lists prose and poetic and the forms varied by time period. Earlier documents were more like to be in prose style, while later ones were more likely to be in lists, which often contained incomplete sentences lacking subjects such as woman, women, she. For example, The 2002 Society for Cutting Up Boxes “ SCUB is all for... 1. IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF LIFE 2. FASHION 3. COMMUNICATION 4. REVOLUTION 5. DESTRUCTION” Similarly the play with language in the poetic manifestos, the smallest group which varied little between time periods, also led to less use of these words. For example, the 1977 MANIFESTO FOR A RADICAL FEMININITY FOR AN OTHER CINEMA the precept “ A feminine culture can only be rupture from dominant culture” ss followed only by fragments of sentences ”Can only be the negation of dominant language. Can only reject the processes of dominant art. Can only let arise all that is oppressed by social order: body, desire, sexuality, unconscious, singularities. Can only let the rebellion of the repressed fracture the norms of expression.”

These findings seemed to account at least in part for the decline in content about female people, but what about the overall content of the post 1990 manifestos?

I created what I think of as the one chart to rule them all As we can see, the latter period includes an increase in the body (in grey) and science technology (blue), as the BITCH MUTANT MANIFESTO (1994) proclaims “Pretty pretty applets adorn my throat. I am strings of binary.” The prevalence of the body and technology is not particularly surprising, but the differences are not perhaps as great as scholarly discussion of this shift might indicate. This visualization also allows us to start to get towards some answer to one of my original questions are there influences or relationships that we might trace among the manifestos? While Bitch Mutant Manifest is admittedly a singular document that has no precise tag matches in this manifesto set, 70% of the documents do.![]()

![]()

Nine manifestos (far left of slide) have content in all areas which provides one place to look at changes and continuity, consider the 1969 insistence “I am an artist. I am a woman. I am a wife.” or 1972 “But we are women and WE ARE SUBJECTS and will portray ourselves as such” The writing into existence an identity denied, against the 1992 disbanding of “Eva and Co – women´s artist´s group and feminist cultural magazine, but also the 2013 Mundane Afrofuturist manifesto “An awakening sense of the awesome power of the black imagination: to protect, to create, to destroy, to propel ourselves towards what poet Elizabeth Alexander describes as “a metaphysical space beyond the black public everyday toward power and wild imagination.”

As with all my digital projects, I came to the end of this work at the place I wished I was starting, with a close analysis of these kinds of polymorphic disjunctions and adaptations. When I pick this project back up again, I will also try to get back to my original question - How did manifestos circulate through the feminist art movement or influence subsequent manifestos?

At this point the digitized periodicals I had access to contain very few references to manifestos in general and only one from Deepwell’s anthology appeared, the seldom mentioned A Manifesto For The Feminist Artist by Rita Mae Brown. The manifestos mentioned most were instead from the art world, futurists and surrealists in particular, and from the women’s liberation movement, SCUM and the Fourth World Manifesto. Therefore to contextualize what I found here a follow up project would not only add more feminist art manifestos, but also a comparison set drawn from both women’s liberation and art world manifestos.

Appendix 1

List of Manifestos from Feminist Art Manifestos (Deepwell, ed).

Mierle Laderman Ukeles Manifesto For Maintenance Art 1969

Agnes Denes A Manifesto 1969

Michele Wallace Manifesto Of Wsabal 1970

Nancy Spero Feminist Manifesto 1970-71

Monica Sjoo And Anne Berg Images On Womanpower 1971

Rita Mae Brown A Manifesto For The Feminist Artist 1972

Valie Export Women's Art: A Manifesto 1972

Feminist Film And Video Organizations Womanifesto 1975

Klonaris / Thomadaki Manifeste Pour Une Féminité Radicale Pour Un Cinéma Autre 1977

Carolee Schneemann Women In The Year 2000 1977

Z.Budapest, U.Rosenbach, S.B.A.Coven First Manifesto On The Cultural Revolution Of Women 1978

Ewa Partum Change, My Problem Is A Problem Of A Woman 1979

Women Artists Of Pakistan Manifesto 1983

Chila Burman There Have Always Been Great Black Women Artists 1986

Eva And Co The Manifesto 1992

Vns Matrix Bitch Mutant Manifesto 1994

Violetta Liagatchev Constitution Intempestive De La République Internationale Des Artistes Femmes 1995

Old Boys Network 100 Anti 1997

Lily Bea Moor (Aka Senga Nengudi) Lilies Of The Valley Unite! Or Not 1998

Dora Garcia 100 Impossible Artworks 2001

Subrosa Refugia: Manifesto For Becoming Autonomous Zones 2002

Orlan Carnal Art Manifesto 2002

Rhani Lee Remedes The Scub Manifesto 2002

Factory Of Found Clothes Manifesto 2002

Feminist Art Action Brigade Manifesto 2003

Mette Ingvartsen Yes Manifesto 2004

Xabier Arakistain Arco Manifesto 2005

Yes! Association/Föreningen Ja! Jämlikhetsavtal #1 The Equal Opportunities Agreement #1 2005

Arahmaiani Letter To Marinetti And Manifesto Of The Sceptics 2009

Guerrilla Girls Guide To Behaving Badly 2010

Julie Perini Relational Filmmaking Manifesto 2010

Elizabeth M. Stephens And Annie M. Sprinkle Ecosex Manifesto 2011

Lucia Tkacova And Anetta Mona Chisa 80:20 2011

Silvia Ziranek Manifesta 2013

Martine Syms Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto 2013

Appendix 2 Items By Country

Australia 1

Denmark 1

France 3

Germany 3

Indonesia 1

Japan 1

Pakistan 1

Poland 1

Romania 1

Russia 1

Spain 2

Sweden 1

United Kingdom 3

US 15

![]()

This relative decline in feminist art manifestos of the word men or male raises the question of what happened to this an oppositional discourse? Had disappeared it? I was also intrigued by the lack of bursts in the post 1990 period at all, no matter how the software settings were tweaked, which indicated relatively little in common in these documents as compared to the earlier documents.

I then turned to a semantic tagging software program to try to get to how the language and content of the manifestos shifted over time.

As expected the earlier set of documents are fairly consistent in this content, but it certainly has not disappeared after that time. In fact art and obligation/necessity continue even as female people do so less. Do we then have then feminist art manifestos without women? In a sense yes. One quarter of the manifestos have no content tagged as “female persons” They are anchored in the mid 1990s to very first years of the 21st century. To those of us working on feminist art during that period, the early years of that era will be remembered as one of both considerable backlash against 1970s feminist art even as artists continued to explore feminist issues.

Two other hypotheses occurred to me, either authors no long feel the need to no need to hammer away at the message women can be artists, and thus less mention of women in general, or perhaps there might be a relationship of form and content.

I categorized the manifestos into three forms, lists prose and poetic and the forms varied by time period. Earlier documents were more like to be in prose style, while later ones were more likely to be in lists, which often contained incomplete sentences lacking subjects such as woman, women, she. For example, The 2002 Society for Cutting Up Boxes “ SCUB is all for... 1. IMPROVING THE QUALITY OF LIFE 2. FASHION 3. COMMUNICATION 4. REVOLUTION 5. DESTRUCTION” Similarly the play with language in the poetic manifestos, the smallest group which varied little between time periods, also led to less use of these words. For example, the 1977 MANIFESTO FOR A RADICAL FEMININITY FOR AN OTHER CINEMA the precept “ A feminine culture can only be rupture from dominant culture” ss followed only by fragments of sentences ”Can only be the negation of dominant language. Can only reject the processes of dominant art. Can only let arise all that is oppressed by social order: body, desire, sexuality, unconscious, singularities. Can only let the rebellion of the repressed fracture the norms of expression.”

These findings seemed to account at least in part for the decline in content about female people, but what about the overall content of the post 1990 manifestos?

I created what I think of as the one chart to rule them all As we can see, the latter period includes an increase in the body (in grey) and science technology (blue), as the BITCH MUTANT MANIFESTO (1994) proclaims “Pretty pretty applets adorn my throat. I am strings of binary.” The prevalence of the body and technology is not particularly surprising, but the differences are not perhaps as great as scholarly discussion of this shift might indicate. This visualization also allows us to start to get towards some answer to one of my original questions are there influences or relationships that we might trace among the manifestos? While Bitch Mutant Manifest is admittedly a singular document that has no precise tag matches in this manifesto set, 70% of the documents do.

Nine manifestos (far left of slide) have content in all areas which provides one place to look at changes and continuity, consider the 1969 insistence “I am an artist. I am a woman. I am a wife.” or 1972 “But we are women and WE ARE SUBJECTS and will portray ourselves as such” The writing into existence an identity denied, against the 1992 disbanding of “Eva and Co – women´s artist´s group and feminist cultural magazine, but also the 2013 Mundane Afrofuturist manifesto “An awakening sense of the awesome power of the black imagination: to protect, to create, to destroy, to propel ourselves towards what poet Elizabeth Alexander describes as “a metaphysical space beyond the black public everyday toward power and wild imagination.”

As with all my digital projects, I came to the end of this work at the place I wished I was starting, with a close analysis of these kinds of polymorphic disjunctions and adaptations. When I pick this project back up again, I will also try to get back to my original question - How did manifestos circulate through the feminist art movement or influence subsequent manifestos?

At this point the digitized periodicals I had access to contain very few references to manifestos in general and only one from Deepwell’s anthology appeared, the seldom mentioned A Manifesto For The Feminist Artist by Rita Mae Brown. The manifestos mentioned most were instead from the art world, futurists and surrealists in particular, and from the women’s liberation movement, SCUM and the Fourth World Manifesto. Therefore to contextualize what I found here a follow up project would not only add more feminist art manifestos, but also a comparison set drawn from both women’s liberation and art world manifestos.

Appendix 1

List of Manifestos from Feminist Art Manifestos (Deepwell, ed).

Mierle Laderman Ukeles Manifesto For Maintenance Art 1969

Agnes Denes A Manifesto 1969

Michele Wallace Manifesto Of Wsabal 1970

Nancy Spero Feminist Manifesto 1970-71

Monica Sjoo And Anne Berg Images On Womanpower 1971

Rita Mae Brown A Manifesto For The Feminist Artist 1972

Valie Export Women's Art: A Manifesto 1972

Feminist Film And Video Organizations Womanifesto 1975

Klonaris / Thomadaki Manifeste Pour Une Féminité Radicale Pour Un Cinéma Autre 1977

Carolee Schneemann Women In The Year 2000 1977

Z.Budapest, U.Rosenbach, S.B.A.Coven First Manifesto On The Cultural Revolution Of Women 1978

Ewa Partum Change, My Problem Is A Problem Of A Woman 1979

Women Artists Of Pakistan Manifesto 1983

Chila Burman There Have Always Been Great Black Women Artists 1986

Eva And Co The Manifesto 1992

Vns Matrix Bitch Mutant Manifesto 1994

Violetta Liagatchev Constitution Intempestive De La République Internationale Des Artistes Femmes 1995

Old Boys Network 100 Anti 1997

Lily Bea Moor (Aka Senga Nengudi) Lilies Of The Valley Unite! Or Not 1998

Dora Garcia 100 Impossible Artworks 2001

Subrosa Refugia: Manifesto For Becoming Autonomous Zones 2002

Orlan Carnal Art Manifesto 2002

Rhani Lee Remedes The Scub Manifesto 2002

Factory Of Found Clothes Manifesto 2002

Feminist Art Action Brigade Manifesto 2003

Mette Ingvartsen Yes Manifesto 2004

Xabier Arakistain Arco Manifesto 2005

Yes! Association/Föreningen Ja! Jämlikhetsavtal #1 The Equal Opportunities Agreement #1 2005

Arahmaiani Letter To Marinetti And Manifesto Of The Sceptics 2009

Guerrilla Girls Guide To Behaving Badly 2010

Julie Perini Relational Filmmaking Manifesto 2010

Elizabeth M. Stephens And Annie M. Sprinkle Ecosex Manifesto 2011

Lucia Tkacova And Anetta Mona Chisa 80:20 2011

Silvia Ziranek Manifesta 2013

Martine Syms Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto 2013

Appendix 2 Items By Country

Australia 1

Denmark 1

France 3

Germany 3

Indonesia 1

Japan 1

Pakistan 1

Poland 1

Romania 1

Russia 1

Spain 2

Sweden 1

United Kingdom 3

US 15

No comments:

Post a Comment