Longer version of 10 minute talk given Nov 15 at American Art History and Digital Scholarship: New Avenues of Exploration watch Video of the event or check out slides for revised version done at ThatCampCAA

I revisit this topic in the forthcoming essay "Feminist Artists and Network Analysis," Artlas

Before I start I want to thank the people who assisted me with Visualizing Schneemann, Kristine Stiles, who edited Schneemann's correspondence, Laura Sells and Diane Grosse, from Duke University Press, who helped me secure an e version of the text for research, E.J. Guerra who helped with data processing, but most of all my indefatigable graduate assistant Maggie Byrd.

For the past 20 years I’ve been studying the links between feminist art and the women’s liberation movement. During a sabbatical a few years ago as I travelled from archive to archive I realized the centrality of Carolee Schneemann to the networks I write about. When I saw the edited collection of her letters, I began to think about about visualizing the circles. I hoped that a network analysis might reveal more about her overlapping circles and that corpus linguistics might reveal interesting aspects of her as female artist in a largely male milieu.

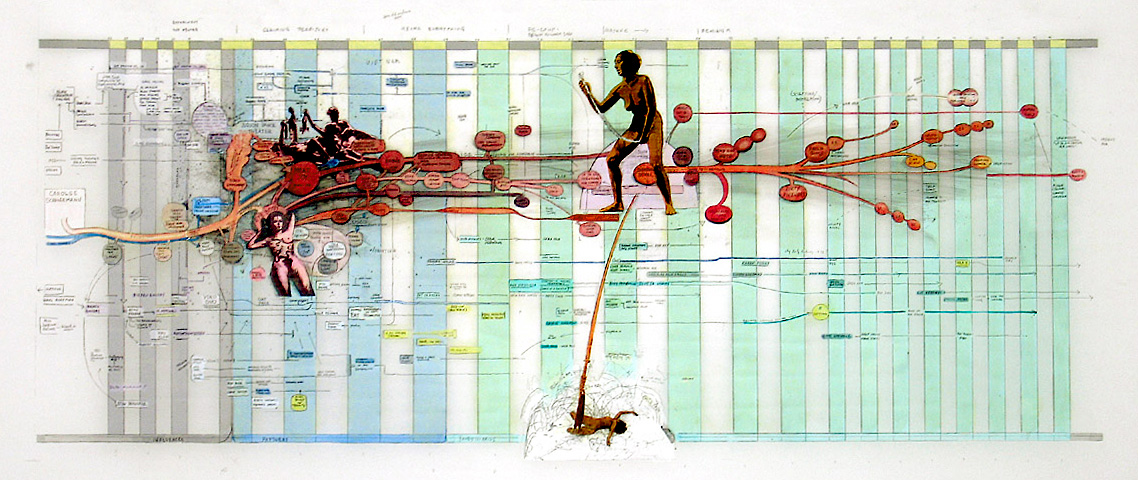

I am not the first to notice the centrality of Schneemann. This work by Ward Shelley “laid out the people that Carolee claimed as her predecessors, then her contemporaries, that she worked with together to develop these ideas.”

|

| Carolee Schneemann, Chart 1. Ward Shelley, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum |

Prior visualizations point to complexity of positioning an artist like Schneemann who has been assigned to 10 subject headings in SNAC. The visualization of metadata from some major archives reveals connections between the people she is also connected to, indicating the numbers of circles I am looking to visualize.

I began with Kristine Stiles' edited volume of Schneemann's correspondence from 1956-1999.

I requested e copy of text from Duke, and received PDF which I converted to plain text and HTML using ABBYY Finereader. After looking into possibility of scraping the file, the indefatigable Maggie Byrd hand cleaned the text and separated the letters into individual files. She also compiled metadata on the correspondents. I ran the corpus through Stanford natural language processing named entity recognition software which tagged for places, names, and organizations. We used linux to extracted the tagged entities, which I then hand cleaned and ran through RAW to yield different visualizations. I also used Antconc, a concordance software to do a preliminary corpus linguistics analysis of Schneemann’s letters. I initially intended to use Gephi to visualize those results but realized ultimately that Antconc produced more legible visualization.

Schneemann made carbon copies of all of her letters and saved those from her correspondents throughout her life. The full collection is held at the Getty Research Institute, but I had access only to a highly edited collection of only about one-third of her existing correspondence. Stiles views the letters she chose as “historical vagaries” intended to reveal “the nature of the conditions under which real artists live, work, and love.” Stiles seeks to establish Schneemann's centrality to avent-garde art circles. As she notes in the introduction, “As this book goes to press in spring 2010, no museum yet plans to offer Schneemann a retrospective after fifty years of pioneering work.” However in addition, Stiles also highlights “the artist’s furious energy in defense of a woman’s right to represent herself and to control her future … Schneemann’s battle for feminist principles must be considered one of the” themes of the letters.

I ended up with 418 letters in my corpus, and I know some were missed.

Almost twice the number of letters from Schneemann, as from her correspondents appear in the volume. Of the letters from Schneemann, which I’ll be talking about today, about one-third were written to women and about two-thirds to men, although there are almost equal numbers of female and male recipients. This makes the male correspondences denser and richer.

Looking at the primary occupations of the correspondents, it isn’t surprising that artists dominate, but also some other aspects become clearer. While artists split almost evenly male female, art historians tipped female critics, curators, poets all tipped male. Wife is as large a category as dancers for the women.

This graph looks at Schneemann's circles by the largest numbers of letters from correspondents, combined with the "circles" they represent. Schneemann's life long friendship with three men, the composer James Tenny, the filmmaker Stan Brakhage and the Poet Clayton Eshleman are the largest in the edited collection which tilts her "circles" towards film, music, and poetry. Only one woman, Naomi Levinson, appears in the largest correspondences.

So far, Schneemann's circles are heavily male. This visualization reveals that the content of her letters, as opposed to simply the correspondents, as extracted by NER software are still heavily male. The pink circles represent women, although five are mythical goddesses. This visualization relies only on data extracted by NER although I hand cleaned and combined the results to yield these names. NER definitely missed some names.

A final visualization from the letters relies on geographic locations mentioned in the letter as identified by NER. It reveals the deeply international reach of her circles.

To get into the letters required another process all together. I relied on corpus linguistics the study of language as expressed in samples (corpora) of "real world" text. Basically I looked for word patterns in the letters based on statistical probabilities.

I’m going to be talking about two corpus linguistic concepts, collocates, words that appear together at frequency greater than random chance in a body of texts and keywords, unusually frequent words in a corpus when measured against a reference corpus. My comparisons here are based on looking at her letters as compared the letters written to her.

Keyword analysis reveals that “The” appears less frequently in letters to CS than in the letters from her which makes it a negative key word. That means Schneemann used “THE” more frequently than her correspondents did.

That set me off looking at the collocates for THE. In the above graphic, the y axis shows actual frequency as compared to expected frequency in text of that size. higher on the Y axis mean that the word appeared more frequently than would be expected The x axis represent the the statistical probability of word appearing together by random chance. The further right means the less likely that co-occurrence is chance.

As we can see in the upper right corner the pink circles that cluster together away from the grey (which represent letters to schneemann) she had a distinctive way of using THE PAST.

THE PAST is particularly interesting because of Schneemann’s deeply historical work, both in her reworking on canonical art history, such as SLIDE Cezanne She was a Great Painter (c 1975)

and in her efforts to revision prehistory, as in Unexpectedly Research (1962-1992)

I identified five ways “the past” appeared in her letters

One of the first appearances of “the past” to the filmmaker Stan Brakhage in which she writes of Cezanne’s influence, an ongoing theme of her letters. She continues in this art historical vein, with the past legacies of artists proving both inspirational and burdensome, and these remarks appear in letters to both men and women.

The past as personal torment reflects her efforts to reconcile artist with personal relationships often with male partners who were also artists. Not surprisingly these uses of "the past" appear in letters to men, usually her male partners.

The past to the present reflects the framing of the past as a resource in her work, her work as a mediation on past and present. This usage appears primarily to men save for one to Barbara Smith, which is not particularly surprising because in her formative artistic years, many of her close influences were men, paritucularly as I indicated, her three most frequent correspondents included in this volume.

Perhaps the absolute most fascinating aspect uses of the past though are in the letters she wrote to Naomi Levinson in which the past become a revelatory frame to her insights.

For example she ends a letter in which she writes extensively of Jane Brakhage as a sort of foil, the non artist woman in their foursome and the burdensome aspects of femininity she represents, particularly that of motherhood, by framing a discrete unit of time “the past week” as she asks Naomi to validate her insights. Similarly, after an intense weekend between the two couples in which many of the resentments of past years came to a head, Schneemann comes to understand the idea that it is “not to destroy the past but to put it back where it belongs.” And as she made clear to Brakhage many years later her past would be put where it belonged by her only, One of the lovely parts of the correspondence is to see her shift to attitudes towards Jane which do a complete reversal.

Beginning in the last 1980s, CS began what she described at one point as falling through “my own historic rabbit hole “ with feminist critics in particular not recognizing her place in art history. Fittingly the last use of “the past” in a letter to 1999 to Cindy Carr in which she both thanks her for including her in an article, but expressing her dismay at the “the current Lacanian cul-de-sac denying female authenticities” and “her perplexities” at the “eroticized feminine” as “abjection” in recent feminist art. She also notes her own historical positions, she has had “only two works have been purchased by U.S.A. Museums” and thus tis “amazed …. at the gallery trajectory representing younger women artists who create assertive, in your face, hostile body representations, and the art world is rewarding this work!” However, she ends asserting “Who the fuck are we kidding? Between Tracy Emin in the bathtub and Karen Finley as chocolate edible Playboy feature, where do we locate an envisioning feminist politics?”

Indeed the last letters of the correspondence reflect wide range of women, artists, scientists, critics within the broad reach of Schneemann’s circles, mixing in equal part elder feminist remonstrations with elegiac Remembrances of Things Past as she ponders her place (or lack of) in art history.

I’ve shied away from answering definitively either of the questions I posed at the start of my study due to the limited and highly selected/edited letters I had access too. However, I suspect that some things probably wouldn't change, such as the strong influence of Brakhage, Tenney, and Eshleman in Schneemann's early years. However I also know that more correspondence with women exists and I'm interested in how the influences on Schneemann shifted in the 1970s when her correspondence with the men appears to have dwindled.

I’m also curious to compare another significant collocate “the first” which is another interesting historical marker that makes a fascinating juxtaposition to "the past." Finally, I want to include Schneemann's published writings in the corpus linguistics analysis, but also in visualizations of her citations and references to people and places in the texts.

Although I didn't have time to share them in the presentation, the question of Schneemann's larger position within the feminist community of knowledge producers also intrigues me. The organizations mentioned in the book don't overlap these areas, but I know from the archives that Schneemann attended many feminist conferences, such as the Scholar and the Feminist, and was involved in feminist art publications, like Heresies.

I also really wanted to talk about data visualization as a tool in DH. The above two images show the same data represented two ways. The lower is Gephi, the "hot" tool of network analysis, while the top is the relatively easy to use Raw interface. Which seems clearer?

No comments:

Post a Comment